by Phillip Starr

In kyudo (Japanese archery; “the Way of the bow”) the object is quite dissimilar to that of Western archery. The beginning of archery in Japan is prehistoric. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (ca. 500 BC – 300 AD). Although the familiar katana is associated with the samurai (and sometimes referred to as the “samurai sword”), the bow was the original weapon of the warrior class.

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school of Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery).

From the 15th to the 16th century, Japan was ravaged by civil war. In the latter part of the 15th century Heki Danjō Masatsugu revolutionized archery with his new and accurate approach called hi, kan, chū (fly, pierce, center), and his footman's archery spread rapidly. Many new schools were formed, some of which, such as Heki-ryū Chikurin-ha, Heki-ryū Sekka-ha and Heki-ryū Insai-ha, remain today. During the Edo period (1603–1868) Japan was turned inward as a hierarchical caste society in which the samurai were at the top. There was an extended era of peace during which the samurai moved to administrative duty, although the traditional fighting skills were still esteemed. During this period archery became a "voluntary" skill, practiced partly in the court in ceremonial form, partly as different kinds of competition. Archery spread also outside the warrior class. The samurai were affected by the straightforward philosophy and aim for self-control in Zen Buddhism that was introduced by Chinese monks. Earlier archery had been called kyūjutsu (the skill of bow), but monks acting as martial arts teachers led to creation of a new concept: kyūdō (the Way of the bow).

Kyūdō practice, as in all budō, includes the idea of moral and spiritual development. Today many archers practise kyūdō as a sport, with marksmanship being paramount. However, the goal most devotees of kyūdō seek is seisha seichū, "correct shooting is correct hitting". In kyūdō the unique action of expansion (nobiai) that results in a natural release, is sought. When the technique of the shooting is correct the result is that the arrow hits the target. To give oneself completely to the shooting is the spiritual goal, achieved by perfection of both the spirit and shooting technique leading to munen musō, "no thoughts, no illusions". This however is not Zen, although the Japanese bow can be used in Zen-practice or kyūdō practised by a Zen master. In this respect, many kyūdō practitioners believe that competition, examination, and any opportunity that places the archer in this uncompromising situation is important, while other practitioners will avoid competitions or examinations of any kind.

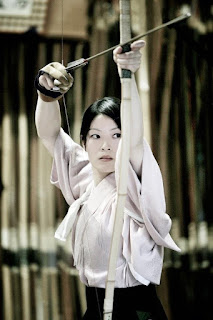

Unlike Chinese, Korean, and Mongolian bows (which are rather short), the Japanese bow will run from 84” to 97” in length. When I visited Japan in 2016, I saw several young ladies dressed in kimono and carrying very long silk or cotton bags, which contained their bows. They would take the subway trains to their classes and nobody thought anything of it.

And unlike Western archery, the primary object of kyudo is not necessarily to hit the mark (“bull's eye”). It is an art steeped in ritual and every aspect of it is pregnant with meaning. Zen-like in its approach, the focus is on strengthening, forging, and tempering the spirit. Each movement (including the steps taken to the spot from which the archer will shoot, nocking the arrow, and virtually everything else) is perfected and polished for its own sake. It is said that when the mind is ready, the arrow will release itself. In time, accuracy comes naturally.

It is rather the same in all forms of budo. However, we Westerners tend to focus too much on hitting the mark rather than perfecting each tiny movement. In our forms, we often rush through to the end, thinking something like, “There! I finished that form.” But the truth is far different. We did not take time to gently polish each movement, to experience and “taste” it. We hurry, like a child in a candy store...filling our mouths with so many candies that we can scarcely taste any one of them. Each candy (and movement) must be savored...delicately at first. Like the arrow in kyudo, accuracy will come along naturally.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment