by Phillip Starr

In most

contemporary martial disciplines, there's a lot of emphasis placed on

exactly, precisely how a given technique is to be performed. To be

sure, this is necessary when first learning a technique or movement

but oftentimes, practitioners get stuck in this particular rut.

Their minds focus on whether or not they (or someone else) do the

movement exactly so. This stunts their growth and becomes a bad

habit that can be very difficult to break. They begin to think of

their techniques and movements in terms of exactly how the foot

should be placed, and so on. Without necessarily being consciously

aware of it, they're focusing on learning and practicing the “outer

shell” of their particular martial art. Many of them never

progress beyond this stage...like an egg that never hatches.

This isn't to say

that students should be free to perform the various techniques and

movements however they wish...I call that the “general idea”

approach. Executing a particular punch or kick must necessarily be

done in a very specific way. But once that stage has been reached,

students must move beyond it. Many never do (and some go on to

become instructors). This anal retentiveness is very common within

the neijia (internal Chinese martial arts) community. A great many

of them focus their attention almost entirely on exactly how the feet

(and even the toes) are to be placed, and so on. Very nitpicky.

Very. Nitpicky. Too nitpicky.

What should be

focused on after the student is able to perform the technique

properly is/are the principle(s) involved. Without this

understanding, he/she may well be doing the technique or movement

incorrectly although it may have the outward appearance of

exactitude. Unfortunately, many of those who teach aren't altogether

certain themselves of just what or which principle(s) are involved.

They got stuck themselves in the rut of “technique.”

Others concern

themselves with how they LOOK when they perform the

technique/movement. To them, it's about cosmetics. They're

concerned with “looking good.” This path leads to nowhere. I

laugh when I tell people that the southern kung-fu systems are

actually rather homely unless you know what to look for...there are

no jumps, twirls, flying kicks, or any of that. No make-up. No

“styled hair.” Real martial arts are oftentimes rather plain or

even homely...

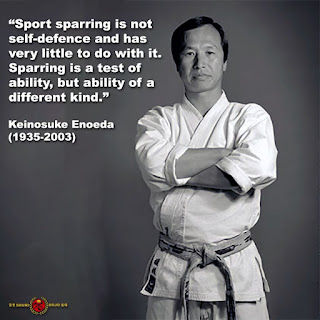

Then there are

those who, after learning how a technique or movement is performed,

get all tangled up in combat application and self-defense. This

becomes their new polestar. Certainly, understanding application and

being able to practically use the technique is very important, but

it's not the end point. Not yet.

They miss the

importance of “feeling.” That is, how the technique/movement

“feels” inside their bodies and how it affects (different areas

of) their bodies. To do this requires a good deal of patience (which

many aspiring martial arts “masters” seem to lack) and

perseverance. One must “listen” and “taste” the

technique/movement. Oftentimes, the flavor is rather subtle, so it's

important to pay attention.

The

technique/movement may LOOK right – it may even look really cool –

but it's nothing more than a doughnut. Nothing inside. Kind of like

a politician. Practice it SLOWLY and FEEL how it affects different

parts of your body. If you know the principle(s) involved in its

execution, you should be able to feel them easily. You might be

surprised to discover that they're just not there! You might

discover certain parts of your body being involved in the technique

when they shouldn't be. If you listen carefully and savor the

movement, you may be surprised at what you find.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)